What middle-aged women see when they look in the mirror

Who gets to decide what women should look like?

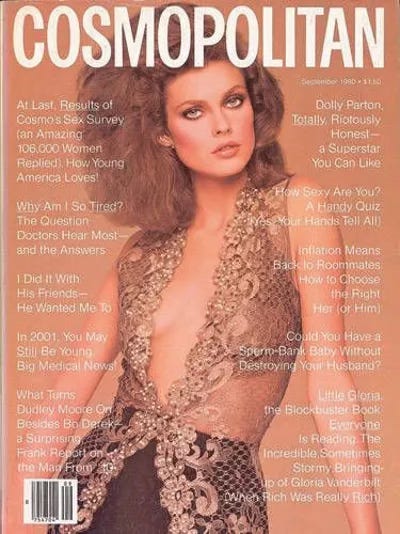

I was born in 1971, which means I came of age in the era of the supermodel, a new breed of fashion icon that transcended the industry and infiltrated pop culture. These women, all amazingly tall and impossibly thin, embodied – and sold – a mythical vision of female beauty that no mere mortal could attain. I covered my bedroom walls with posters of these women – Cindy Crawford, Christie Brinkley, Naomi Campbell, Paulina Porizkova – not because I wanted them, but because I wanted to be them. I wanted men to look at me the way they looked at them.

It was unlikely, however, that I would grow up to have long limbs, glorious hair and chiseled features. My genetic makeup, coded to help me survive a potato famine, gave me a stout but solid body that would make me an excellent candidate to survive a season of Alone, but not so much America’s Next Top Model. But being an endomorph did not spare me – or any woman my age – from the suffering inflicted by the 80s supermodel culture. What we were taught by magazines, television, ads and music videos – about how our looks and value were inherently intertwined – still shapes the Gen X generation.

Starting in the 80s, as smoking subsided and lifespans grew longer, capitalists saw a marketing opportunity to exploit. The fitness industry boomed, from body building to aerobics (unsurprisingly, in the 80s both anorexia and bulimia appeared for the first time in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; in the 90s, anorexia was associated with the highest rate of mortality among all mental disorders); the term "anti-aging" began appearing on every beauty product; and music videos, which aired nonstop after the advent of MTV, depicted teen girls and young women as groupies, cheerleaders, strippers and sex workers. Women over 40 were either not represented in entertainment, or they were portrayed as past their prime – no longer desirable and, therefore, no longer valuable.

What else entered the zeitgeist in the 80s? The term “the male gaze.” The concept was originally coined by feminist film theorist Laura Mulvey in her essay exploring how men’s domination of the film industry resulted in representations of women from a masculine point of view. In the intervening decades, the term “male gaze” evolved into a shorthand way to reference all of the negative psychological consequences of patriarchy on women, including unrealistic body image standards, objectification and ageism.

Even 40 years later, that “male gaze” continues to shape our culture. And the messages women my age are getting about our bodies, our looks and our societal value are still confusing. We’re told we need to be physically fit and attractive, but also mindful and enlightened. We’re told that perimenopause and menopause are a time of life we should embrace, but also that we should get through it without gaining weight, even if that means taking Ozempic. We’re told it’s ok to be our natural, aging selves, but even our general practitioners and OB-GYNs push skin procedures on us in their offices. So it's no wonder then that Gen X women who are now in their forties, fifties and sixties are having more plastic surgery procedures than any other subset of Americans, including Baby Boomers and Millennials.

I, myself, have bought into this messaging. Nearly every day for the past 35 years, I’ve put on a full face of makeup, including eyelashes. I color my gray hair every four weeks. Since turning 40, I’ve gotten a “light dusting” of Botox every three months or so. I experimented with fillers after an aesthetician told me my face was “deflated,” had my eyebrows microbladed, and withstood laser and ultrasound procedures so invasive they made me look like an extra on “The Day After.” All of this is, of course, on top of daily workouts and watching what I eat. Just writing this paragraph makes me realize that in addition to being incredibly expensive, courting the male gaze is exhausting.

It's easy to feel shame about this. I’m unsure if I’m doing what society tells me or if I’m doing what makes me feel good about myself. I do feel good about the way I look and feel at 53, but who am I comparing myself to? A younger version of myself? Selfie culture on social media? Supermodels? These questions are made even more complicated by the fact that there’s currently a whole cadre of famous women – many of them former supermodels – who claim to support a “natural beauty revelation.” Jamie Lee Curtis, Halle Berry, Selma Hayek, Emma Thompson, Julia Roberts, Jodie Foster, Kristen Stewart and Pink have derided aging interventions. Pamela Anderson recently stopped wearing makeup as a way to “free” herself from beauty standards and Justine Bateman has said that women who choose to get plastic surgery are “people pleasing.”

But are these women actually shifting the narrative by creating a new “female gaze,” or are they simply finding new and more ways to police the way women look and the choices we make, but with a more virtuous bent? At the end of the day, isn’t every comment about a woman’s appearance simply a byproduct of the patriarchy? Because with all of the respect in the world to women like Anderson (who, ironically, just landed a spokesmodel role for Smashbox, a makeup company) and other traditionally beautiful women who promote “natural beauty,” it seems like it’s probably a whole lot easier to fight the status quo when, A) you’re naturally beautiful, and B) you’ve already created financial security by soliciting the male gaze.

A recent survey of over 2,000 Americans found that while 70 percent of men report feeling unconcerned with aging, only 50 percent of women report feeling the same. The same survey found that while an overwhelming majority of women had no trouble equating old age with beauty, only 65 percent of men agreed. In the light of this data, supermodels and former “sexiest women alive” preaching to everyday women about beauty and aging standards seems like a Pyrrhic victory in the face of the patriarchy. The real victory, it would seem, would be to stop equating a woman’s worth to her physical appearance all together. Because at the end of the day, don’t we want to define the “female gaze” as the ability to look at ourselves and know that no matter what we look like, our value isn't determined what we see in the mirror?

Let me know what you think in the comments.

I think you have it right. When we choose to have a battle over which has more value--looking younger (with treatments) or looking natural without, it’s still a conversation that centers a woman’s value on appearances. And meanwhile the men are unconcerned about aging because their value has never been about that. In media, where is there an opportunity to specifically choose to center middle age women and their wisdom, experience, skill, ingenuity--and will it sell? In a small way, I like Julia Louis-Dreyfus’ podcast which tries to do this. Can women with power change the conversation for the rest of us?

I graduated highschool the year you were born. I hit middle school with Twiggy as our ideal...sigh. When the 80s super models hit, they were touted to a us as larger, more realistic females. I never fit any of the ideals. Now at 70, I wear no makeup, my long hair is grey and I'm still overweight. I am comfortable in my skin.